法王新闻 | 2022年04月

『第7届谶摩春季』噶玛巴米觉多杰自传•第八天第二堂课

『7th Arya Kshema』AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL VERSES OF KARMAPA MIKYÖ DORJE•8-2

རྗེ་བཙུན་མི་བསྐྱོད་རྡོ་རྗེའི་རྣམ་ཐར། བདེ་བྱེད་མའི་དཔྱིད་ཆོས། ཉིན་བརྒྱད་པ།

時間:2022年04月04日 04th April, 2022 22:30-23:30(北京时间)

中文笔录:噶玛妙竹

Uploaded on 4/15/2022

Last updated on 11/8/2022

什么是“清净心”?

都听得到吗?好。

那么就像刚刚说的,我们说“利他”,对于最好的、最殊胜的利他,每个人的认知都不同。就是我们自己从小到大的认知也都不同。小时候觉得最好的,到年纪大点,再到老一点,我们觉得最有利的、最好的,也都 不同。所以是不一定的。没有钱的时候,就会希望有钱,那时候觉得有钱最好。但有钱了之后,你会觉得可能另外一个东西是最好的。总是会觉得还有一个更好的。这代表了什么?我们总是觉得有一个最好的, 但实际来说,并没有真的了解到什么是最好的。这就代表我们并不知道什么是最好的,总是再追求另外一个最好的。

什么是“清净心”?

A pure, excellent intention should focus 100% on benefiting others

再来,什么是“清净心”?什么叫做“清净的善心”之类。今天主要讲的是第16个颂文“清净心”,17个颂文主要谈的是“清净的行为”。“清净的行为”常常翻译成“热诚”或“崇高的行为”“崇高的心”。总之,“清净的心”

“崇高的心”指的是完全没有任何私心,无论做任何事情,都是完全以“利他”为目的。如果我们不明白这样一个“清净心”的关键,那么我们很多行为看起来可能是善行,但是到底能不能真的利益到对方,那就不一定了。

所以,“清净心”是我们必须要指出、认识出的,而且知道怎么样做到的关键。

When we say “a pure, excellent intention,” whatever action we may be doing should not be for our own self-interest and should focus 100% on benefiting others. We should think “what can I do to help this sentient being”? If we do not understand the importance of a pure, excellent intention, something might seem virtuous from the outside, but in actuality may not become a virtuous or beneficial activity.

举个例子来说:我们今天要放生一头牛。这样的一个行为是「善」还是「不善」呢?

一般来说,放生的行为它是善,但是很多时候,我们不能只是看行为是善的,就觉得这件事情一定是善,为什么呢?因为放生的时候,譬如说放生这头牛的时候,它不只是身体上的行为,一起的还有你的心念、

动机,还有态度。这些都是和我们的身体行为一起发生的。身体的行为别人看得到,但我们的心念、动机别人看不到。很多时候,就因为动机、心念是别人看不到的,有可能就被我们忽视了。会觉得反正别人看不到,

就觉得动机、心念没有那么重要,就被我们忽视了,这样是危险的!事实上,非常重要的是我们的动机和态度,不止和行为一样重要,甚至动机和态度比行为更重要。

For example, if we perform a life release for an ox, is this task virtuous or not? Outwardly, it appears to be a virtuous action, but action alone does not indicate virtue. When we release the ox, in addition to the external manifestations of the action, there is the internal motivation and intention. Although others can bear witness to the external manifestations of our body and speech, we alone are privy to our own motivation, so there is a great danger of ignoring this aspect. Motivation and intention are actually more important than physical and verbal actions.

为什么这么说呢?首先,你为什么想要放生这头牛?因为你开始有一个行善的动机。如果一开始没有行善的动机,那么也就不会有这样的行为。而且在放生的当下,最重要的不只是放生时这些善的行为,各种

动作、表情,更重要的是我们的内心是不是很清楚“为何要救它”,而“为何要救它”的答案是谁给的?是我们的动机和态度给的。所以,动机和态度就像是“指挥官”,身体、语言和各种的行为只是一个“工具”。

Why do we want to release the ox? This can only be answered by our motivation and intention. Body and speech are merely the tools we use to accomplish our intentions, which are in charge.

举个例子,我们走在路上,这时候来了一台车撞到了我们,稍微碰到、擦撞到,不是很严重,我们稍微摔倒,爬起来。这时候你要去理论,你会去找谁理论呢?你会去找那个驾驶、车主理论,不会去找那台车理论对吧。

你不会站在车前,说:“喂!车子。你干嘛撞我!”这样子的话,别人大概会觉得你脑子有问题。就像是这个比喻,所以,重点是为什么我们要救这头牛,你的动机和态度能够回答。是那个主人,就像那个驾驶能够回答,

不是那个车子,那个身、口的行为能够回答。虽然我们放生那头牛的目的不是处于内心的关爱,真的担心这个牛被杀,怕它痛苦,如果只是做做样子给别人看,那么这种善的行为只是一种伪善、一种相似的善,不能说

是善。为什么不能说是善?就是因为我们的动机。

Similarly, if you are struck by a car, you’re not going to ask the car (a tool) why it hit you; you ask the driver who is in charge. So examine your motivation. What is the purpose of saving the ox’s life? Are you thinking about this particular ox? Is it out of love? Are you thinking “It wouldn’t be right if this ox dies”? If instead you are trying to show off, so that others perceive you as a good person and a good dharma practitioner, your virtuous action becomes a “pseudo-virtue” due to the motivation.

善的质量要好

We need to accomplish virtues that are quality and meet a standard

再来一个,就是善的质量要好。上面我们谈到的,我们可以知道,同样的一个行为,譬如说,同样的放生一头牛的行为。有的人是善,有的人只是相似的善,或者不能说是善。为什么会有这两种结果?最主要取决于

两个因素。一个就是发心或者说动机。发心可以分为两种,一种是开始的发心,或者说“因”的发心。再来是时间上的发心,就是当时的发心。所谓的“开始的发心”,也就是做这件事情的目的是什么?你为什么做这件事?你开始的发心是什么?或者说原因“因”上的发心。再来,时间上的发心是什么?就是你做这件事情当下的态度是什么?就这样两种发心。

Although the actions of our body and speech may be identical, whether the result is a virtue or a pseudo-virtue depends on our motivation and the level of the action. Motivation includes the causal motivation and the immediate motivation. The causal motivation is our aim when we first think about doing the action, while the immediate motivation is our thinking while we do the action. In contemporary language, the level of the action is the quality and the quantity of the action.

会造成不同结果的第二个因素是“程度”,也就是做这件事情的数量多寡,话句话来说,这两个因素现代的话来说,就是善行的“质”跟“量”的因素。 再细的来讲,“质”是什么呢?如果要让善的质要好,一方面来说,就是取决于我们的动机,还有我们的目的,如果清楚,这个“质”就是好的。就像前面谈到,动机有两种,首先,我们开始的目的是什么? 还有是否具备了清净的善心,是否具备一个清净的心。这就是「开始的动机」,所谓的「因上的动机」。这就是我们开始的目的到底是什么?

所以,无论我们做任何事情,最开始我们要清楚地调整好自己的动机,确认自己的动机,也就是我们行善的目的是什么。这是开始的时候要问我们自己的,然后你要有一个很清楚的答案,就像是“自问自答”一样。

你自己要给自己一个清楚的答案,我们行善的目的是什么?是为了让别人变得富有,还是让别人变得有权有势,甚至是为了让别人得到人、天的果位,或者是声闻“解脱的果位”,还是

别人能够得到究竟的佛的果位。这个答案要非常的清楚。

The quality, or authenticity, will depend upon our motivation and aim. Pure, excellent intentions relate to clear, stable, causal motivations. Are we performing the action to make someone else rich and powerful, or to bring them to higher states and true excellence? Or to bring them to buddhahood? The aim must be unequivocal in our minds to achieve results.

如果不谈佛法,只谈世间来说,一个成功的人,没有清楚的目的,他是不可能成功的。一个成功的人,都是因为有一个非常清楚的目标、一个非常清楚的目的,才可能成功的。糊里糊涂的,是不可能成功的。但这不是说,一个修行者,不能去做世间的工作、去赚钱,不是这个意思。我们还是人,还是得生活,生活就必须要赚钱。所以我们不能说“不赚钱”。重点是我们需要赚钱,可以赚钱,但赚钱只是其中的一个目的,而不是我们 全部的目的,就是我们人生的目标不是赚钱。所以,就算我们赚不到钱,也不会因此失去生命的意义,不会。很多人就把赚钱当成了一生全部的目的,赚不到钱了,就失去了生命的意义,很多人是这样子。

对一个修行者来说,短期来说,我们有很多事情要完成;但是究竟的、长远的目标是什么?就是成佛!我们的身体在我们死了之后就没了,会换一个,但是我们的心识是会持续下去的。我们心识的意义也好,或者说我们想要解脱成佛的目标它是不会变的。换句话来说,我们的目标一定要非常清楚。不止是清楚,而且还要非常坚固、坚定。不能说,现在这个目标不错,过几天换一个目标,有时候觉得世间的目标不错,有时候觉得佛法的目标不错。不能这样子换来换去,这样子的话,可能很难成佛。目标很清楚之外,那就不要换来换去,要坚定一个目标,从一而终。

As dharma practitioners, there are many different things that we need to do. But there is just one ultimate aim: achieving the state of Buddhahood. When you die, you exchange your body for the next life, but you don’t exchange your consciousness – it continues. Therefore, you need to make your consciousness meaningful. The essential purpose for your consciousness is to transcend birth and death and reach liberation and achieve the level of buddhahood.

禅宗的故事

Stable aims lead to perfect results

这里有一个故事,汉地的一个故事,中国佛教禅宗的一个故事。有一位禅师,他和他的一些弟子们在一起。他们是农禅生活,所以会自己耕种。一天,禅师就带着弟子们在田里插秧。尼泊尔、印度,很多的僧众

都干过,就是插秧。在田里面一个一个插着,秧要插得很直,很整齐。弟子们插得秧都是歪歪扭扭的,禅师插得秧就好像用尺量过一样,非常的整齐。

His Holiness told a story of a Chinese Zen master and his students, who in the olden days had independent lives and lived off their own means, growing their own food. One day, the master brought his students to plant rice. Each rice seedling must be planted individually in the paddy, in straight rows. After planting, the students’ rice was crooked: some seedlings were in front, others behind, and the rows went this way and that. Meanwhile the master’s rice was planted in a perfectly straight line.

弟子们就很疑惑,问禅师说:“师父,为什么你插的秧苗这么的直、这么的整齐?”

The students wondered about this, and asked the master, “How could you plant rice in such an incredibly straight line? Our rice doesn’t look like that”.

这个禅师就笑着说:“这很简单,你们插秧的时候,眼睛要盯着一个东西,对准插,就可以很整齐了。”

The master started to laugh, “It’s really easy! When you’re planting the rice seedlings, you need to pick a reference point, and focus unwaveringly on that one thing as a target, drawing a path from there. Plant the rice seedlings along that path toward the target”.

弟子们听完就继续插秧,这次插完,竟然是插成一个弯曲的弧线。

The students thought “OK!” and continued planting. After more rows were planted the students noticed another problem: now their rows of rice seedlings curved in arcs and meandered.

禅师就问弟子:“你们有没有看着一个东西呢?”

The master noticed and asked the students, “How did this happen?”

弟子就说:“有的,你刚刚说要看着一个东西,对准,然后跟着插秧。我们就盯着一头水牛,跟着这头水牛,它一边走,我们就一边插。”

The students replied, “Oh master! You said to focus on a reference point. There was an ox in the distance, so we used that as the target for planting the rice.”

禅师就笑着说:“那头水牛,它不是固定的,它是一边吃草,一边走着的。你们在插秧的时候,当然也就跟着这头水牛会移动。所以你们会插成这个样子。”禅师又说:“你们一定要盯着一个非常稳定的、大的目标。盯着它。”

The master scolded, “You students do not understand! The ox is going to move here and there. When the ox moved, your target moved and consequently the rows of rice arced. The target reference point wasn’t stable. You need to focus on something unmoving and stable.”

所以,他们就选定了远处的一棵大树,对准它,果然插的秧苗就非常的直、非常的整齐。

The students noticed a big tree and focussed on that for their measure, once again planting the seedlings. Finally, their rows of rice became perfectly straight, like the master’s.

这里要说的,就是我们的目标要非常的清楚,而且要非常稳定的一个目标。不然的话,有的时候我们的善会增长,但有的时候善又不会增长。

Similarly, our own aims need to be not only clear, but also stable and unwavering. If we don’t have a stable aim then sometimes we may be performing virtue, sometimes non-virtue, sometimes pseudovirtue.

Bamboo评论:大宝常常自比为“牛”,远处的一棵大树指的就是菩提树吧。所以,Bamboo觉得这里的意思是:你做任何事情,都要盯着和对准成就“遍知一切”的佛果,而不是盯着大宝。尤其是现在大宝的讲课视频从人像到声音全是假的之后,你再继续看的话,搞不好就像大宝这里画了一段弯弯曲曲的线,然后拐了个弯又回到原点一样,一无所获。

当然这段话也提醒Bamboo,自己定下的目标就不要变,不管外境如何乱象纷呈。(11/8/2022)

再来,第二个就是我们的发心要清净,发心清净指的是:不带有任何的私心,百分之百都是为了利益他人。这样的一种心就是“清净心”“清净的发心”。我们现在可能没有办法马上升起这样子完全不带任何私心,百分之百

利益他人的心。但是我们要尽力去升起,至少发起百分之五十是要帮助别人的心,这样也是很好的。譬如说,百分之五十是帮助自己,但是百分之五十是帮助别人。先不从这样开始,就做到百分之百利益别人,那是很难的。

你必须先从稍微关心别人一点开始,不要总是想的是自己。稍微关心一点、一点,关心别人多一点、多一点,这样慢慢加上去,才可能做到百分之百。再来行善的时候,我们有多认真、多仔细,还有多关切,这个就是

当下的动机,动机我们说有第二种——时间的动机、当时的动机。

We also need pure, excellent intentions. We should have the clear intention of devoting ourselves 100% to the benefit of others in a way that is unconnected with our own individual needs and self-interest. If the deed is connected with our own benefit, even a little, it is not pure. We also need to ask ourselves whether this is really and truly beneficial to that other being. Of course, this is very difficult to achieve, so we do as much as we can. Even if we can’t have a pure, altruistic intention, we should go more than half-way tobenefit others, thinking that others’ needs are more important than our own. That’s the causal motivation. Then we need to evaluate our assiduousness, precision, and interest while performing the action. This indicates our immediate motivation.

总之,善的质量的优劣,关键就在于我们的动机,刚刚谈到有两种:一种是开始「因上的动机」;接着是做的时候「当时的动机」。所以,我们过去的祖师们,任何时候,无论是讲经说法的时候也好;课诵持咒的时候也好,任何时候

都会强调我们,一开始一定要导正我们的动机,动机一定要清净。因为整个善行的质量好坏,关键就在于我们的动机。

Thus the crucial point determining the level of quality in our actions comes down to motivation. When great masters of the past taught, studied dharma, recited prayers and texts, or performed other activities, they would fix the intention to have a high-quality, virtuous motivation – and we need to do likewise.

行善不是“外在的形式”

The quantity of the action depends upon our minds, not external things

再来提到是我们的数量——量,我们会说这样一个行善的量到底要做到多少?或者规模要做到多大?是什么意思?

The quantity of action refers to the extensiveness or vastness or frequency of the actions that we do.

是说,一个人每天都在放生,一生都数十年如一日,不停地放生,要这样子规模的放生,就做到了很好的量上的放生?不一定、不见得。

Does this mean that a person should do a life release every day for their entire lives? Not necessarily so.

为什么呢?因为这里的「善」和「量」不是外在有形的物质,重点在于说“质量”,要注意这个“质量”。有没有注意到行善时的态度是不是认真;还有做完之后,有没有注意着后续的影响,和结果。

如果这些都不管,没有注意到开始质量,也没有注意行善时态度等等,只是一昧的“我就是要放生”,而且只在乎放生「量」要大、「规模」要大,这样的行为得到的善果不见得就是很好。

The reason is that the extent or quantity of the virtue does not solely refer to the external appearance. It also refers to the level of the action’s quality, the extent of the interest and assiduousness while you do the action, and how much you are thinking about the action. There is also the effect of the action, the results to which the action leads, and so forth. Merely doing as many life releases as you can is not necessarily a great and vast virtuous action.

现在藏地的一个情况就是,因为藏地经济条件、生活也都好了,大家有些钱了,愿意花钱。年供品也好,荟供品也好,一买就是一大堆。还有风马旗、天马旗,挂得也是满山满谷都是,结果整个环境都被污染了,土地、河流都被污染了。

甚至很多时候,一些动物还被天马旗绳子困到而死了。

These days, the economic situation has improved to a certain degree in Tibet. People have money, so they are spending it on beautiful offerings and rituals, smoke offerings, prayer flags and so forth in vast quantities. They put up so many prayer flags that, in the end, they befoul the earth and water and pollute the environment. This can even cause animals to get caught in prayer flags and die.

我觉得这是值得我们想一下的问题。我觉得以前老一辈的人,像是父母亲他们,并不是没有钱买这么大量的供品,主要是我们没有像父母亲他们

一样的虔诚,那样的信心。就是因为我们没有那样的信心、虔诚,所以我们就觉得形式要做大、规模要做大、量要大,“形式至少要做出来,这样才有福德”。问题都出在我们内心的虔诚和信心变小了,所以外在要搞大。

His Holiness expressed that he doesn’t think that our ancestors were unable to make such huge offerings because they did not have as much money as we do today. Rather, our ancestors had a level of pure faith, outlook and belief which we don’t possess. Today, the external quantity of offerings may be huge in terms of numbers.

但这样做能够利益到、帮助到我们的心吗?很难。所以,善的大跟小,和你供养了多少钱,没有太大的关系,而是和你的心放下了多少执著是有关的。是你的心愿意

给予多少有关。不然的话,有钱人好像都是一直在累积善,不见得的,不是你给多少钱。如果我们觉得行善是一定要外在形式上的规模、数量,那我们就应该去看看佛陀六年苦行,在菩提树下的时候,他拥有什么。

他连吃的、喝的都没有,更别说其他的。那他是如何累积福德资粮的?他如何积聚资粮的?我们可以从佛陀身上找到答案的。

But is it virtuous? We need to examine our minds. Is our motivation empty inside? It's not how much money we may have spent; it’s how much sacrifice we are making mentally, and how much generosity we have that matters when gathering the accumulations. When the Buddha spent six years practicing austerities and then sat beneath the bodhi tree, what did he possess? Nothing at all, not even food or drink. It’s important to consider how the Buddha gathered the accumulations.

所以,善的多寡都不是外在形式上搞得多大,还是在于你的心有没有做到。

The quantity of the action therefore does not depend on external things; it primarily depends upon our own minds.

同样的,很多时候我们在“利他”的时候,我们要懂得“因材施教”,还有“因地制宜”来对症下药。不能够太死脑筋,觉得利他的方法只有一种,还

轻视其他的利他的方法,这样是不对的。而是要用各种的方式、多方面的来“利他”、增长善行,这非常的重要。

Likewise, there are various ways of acting virtuously for different kinds of beings in accordance with the time and place. We should not cling to a single virtuous action or type of virtue due to tradition, then disregard or belittle other types of virtue. It is important for us to use various methods to benefit beings and to work from all directions to increase our virtue.

就像现在,大家很注重“营养学”。这个“营养学”很强调我们的饮食要注重营养的均衡,不能够只吃某一类的食物,不行的。举例来说,我们都知道豆制品对身体很好,像是豆腐。

豆制品可以补充蛋白质,还可以补钙,补维生素等等,但是我们不能够因此每天只吃豆制品,因为只吃豆制品的话,可能会引发像是“痛风”这样的疾病。所以,我们在饮食上必须要注意均衡的搭配。

每样东西都要吃,吃一点,而且要适量的吃。如果只吃一种,身体不会很好,就像这个比喻。

We can use nutrition as an example: it is important to balance the quantities and combinations of different types of nutrients. Legumes and tofu are a good source of protein and are helpful for providing calcium and vitamins. But, even though beneficial, if we only eat legumes, there is the danger of worsening rheumatism and aggravating gout. Thus we need to eat various types of foods, and not eat too much of any one kind.

还有我们利他的时候,不要执著在某一个方法上。譬如说:我只放生,或者我只做「焦烟供」。这样子某方面来说也是好,但是只做这个,但又觉得其他不重要,其他方法不好,这样的想法就不好了。我们必须要从不同的方面,还有各种的方式去利他。这样,才是更善,带来的利益才是更好的,更多的。

总之,“利他”的时候,我们必须要多动脑筋,要很灵活,要很放松,要灵机应变,如果缺少深思熟虑,很呆板、固执地行善,是很难真的帮助到别人的。因此,我们在行善的时候,一定要带有智慧的判断。不然,很固执地行善是不行的。

Similarly, when we work to do virtuous things that benefit others, we should not be too attached to only one method or only one class of virtuous actions. We need to do what is most beneficial and has the greatest effect, using our intelligence to be creative and examine before relaxing our mind and performing the action. Thus when we perform virtuous actions, we must examine things well with our prajna.

转清净行为为道用

Taking actions from good intentions as the path

接着是第17个颂文,就是第7个「道用」。

7. ལྷག་བསམ་གྱི་སྦྱོར་བ་ལམ་འཁྱེར།

Taking acting upon good intentions as the path

转清净行为道用

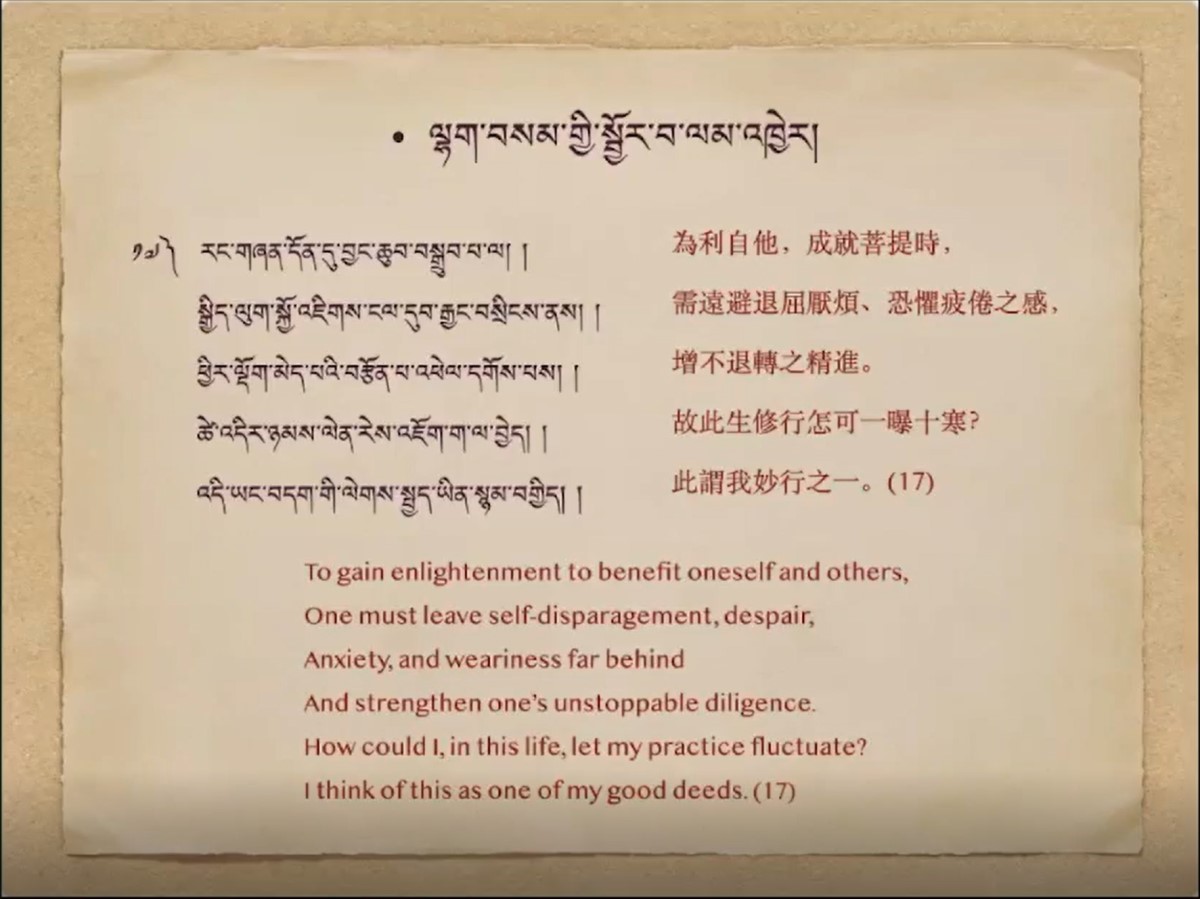

༡༧༽ རང་གཞན་དོན་དུ་བྱང་ཆུབ་བསྒྲུབ་པ་ལ། །

སྒྱིད་ལུག་སྐྱོ་འཇིགས་ངལ་དུབ་རྒྱང་བསྲིངས་ནས། ། ཕྱིར་ལྡོག་མེད་པའི་བརྩོན་པ་འཕེལ་དགོས་པས། ། ཚེ་འདིར་ཉམས་ལེན་རེས་འཇོག་ག་ལ་བྱེད། ། འདི་ཡང་བདག་གི་ལེགས་སྤྱད་ཡིན་སྙམ་བགྱིད། །

To gain enlightenment to benefit oneself and others,

One must leave self-disparagement, despair, Anxiety, and weariness far behind

And strengthen one’s unstoppable diligence. How could I, in this life, let my practice fluctuate?

I think of this as one of my good deeds. (17)

為利自他,成就菩提時,需遠避退屈厭煩、恐懼疲倦之感,增不退轉之精進。故此生修行怎可一曝十寒?此謂我妙行之一。(17)

米觉多杰在世的时候,当时很多人口头上说,是在关心众生、悲悯众生。这些人一开始也学习各种经典,光是学「摄类学」、「辩经」就学了十多年,

接着他们又说要学习密乘的典籍,但其实他们在学的是什么呢?只是学习各种做佛事的,为亡者超荐的仪轨,超荐的各种“弥陀法”。他们并不是

学习甚深的密乘法,只是为了糊口,填饱肚子,去做佛事,而学那些仪轨。学了一段时间之后,又想说,我也学了一些法了,试着要去体验这些内容,

又跑到山里,消失了几年。回来之后,其实之前学的仪轨也好,辩经、摄类学也好,大部分都忘光了,但他还是吹牛,“哦,我山中闭关修行了几年,

我因为闭关实修,开悟了,我的智慧完全开显、开启了。”还在那边吹牛,还为别人说法。说法时怎么说呢?像是三士夫的道次第,我们没办法

那样做。因为那里面说的,什么可以做,什么不可以做,这些「取舍」说的很清楚、很严格,所以他自己没办法再随便乱说。他只能怎么说呢?只能说“佛经当中

说得很多,但都是随便说说的。有些了义,有些不了义,不见得都是了义的、究竟的,所以有些不能当真。修行的时候,需要的是什么?需要的是

得到证悟、得到自在的祖师的口诀才是最重要的。这些证悟者的上师口诀。”换句话说,就是他自己怎么说都可以,就是自己说的,才是真的。

都是为了自己的名声、称赞,才去做很多的讲法、写作、辩论。有这样的人。

During Mikyö Dorje’s time, most people who professed to have love and unbearable compassion would first study the scriptures from the sutra tradition. They’d spend a few decades studying basic logic and debate. Then they’d study the tantric tradition and spend a few years on rituals for the deceased, such as the wrathful and peaceful deities and Amitabha, and not the profound meaning of the tantras – merely rituals for offerings that would support their food. At some point, they’d say, “I’ve done some dharma practice and have internalized the meaning” and then go off to spend a few years in mountain retreat. They would forget their earlier debate logic and most of the rituals, becoming cocky, believing themselves to have a certain degree of experience, with prajna welling forth, and begin to teach dharma. That which we should do and not do is clearly taught in the scriptures on the stages of the path for the three types of individuals. However, instead, they would downplay the Buddha’s words as expedient and not definitive meaning, teaching whatever they want as the guru’s pith instructions for achieving realization. To gain fame, reputation, and pleasure they would engage in teaching and debating.

还有一些人不像是上面说的这些人,还没有能力去写作、讲法、辩论,他们怎么说。说“啊,那太困难了,太花时间了,麻烦,做不到。还没做到那些之前,搞不好就被别人杀了。搞不好生命就没了。太麻烦了,还不如到一个很容易生活的地方,很多施主的地方,有吃、有喝的地方。”说是到那边去利益众生,

但别说利益众生了,主要在那边造恶,造各种的无记业。但别人看了,还觉得说,哇,这个上师过得还不错,还觉得他在利益众生,过得很快乐。

很羡慕他,又有弟子,又有施主。这样的上师他身边有时也蛮多弟子、蛮多人围绕着。

Or some might think, “I can’t do work like teaching, debating or writing. Either someone will kill me or I’ll die naturally before I finish all that work! There’s no point in doing it”. So instead of doing all that work, they would go someplace where they could get all the food, clothing and conversation they might want. They would go where a few women would sponsor them, believing “I’m doing great things for the vast benefit of others”, while generally doing neutral or even unvirtuous activities. Others would think they had a nice life, “This lama has a way of doing good deeds. Maybe it would be great if I were like that?” And so, more people would be attracted, and a large gathering of students would be assembled.

但米觉多杰从来不会羡慕这样的人,反而是很怜悯他们的。(Bamboo批:废话,他都从要饿死的乞丐小孩一跃成了西藏首富,还会羡慕那些小混混吗?)

米觉多杰的行谊是怎么样呢?他怎么样利他的呢?他说,如果本质上是伤害自他的话,就算表面上讲说佛法、修持佛法的话,他也会停止这么去做。所以,真的对米觉多杰有信心的人,他们也会效仿米觉多杰一样,会停止这些相似的善行。

Mikyö Dorje didn’t think such people were important, didn’t aspire to be like them, nor was he swayed nor influenced by them. Mikyö Dorje performed his activity so that if something might cause harm instead of benefiting others, he would stop such actions, as they are not virtue. Consequently, the people had faith in him.

米觉多杰就曾经说:

As indicated in Mikyö Dorje’s own One Hundred Short Instructions, he didn’t consider pseudo-virtues to be important and significant:

“如果能够直接利益到众生是最好,

如果不能,那么间接地去利益众生,避免伤害到他们。我们说法可以;我们思维、修持佛法也可以;或者建立僧团;建立、照顾寺院;兴建佛塔、佛像等等,

这样都是可以的,这些都能够成为成佛的因。不然,如果一开始我们的目的和发心,不是为了利益众生,或者,就算有这样的发心,但是在实际的行为

上,却对众生造成了伤害的话,这样是没有意义的。所以,无论名称是叫什么,「成就者」也好,「修行」也好,这些都是相似的一些行为,这些都要停止。”

At root, it is best to benefit sentient beings directly. If you cannot, then focus on the benefit of sentient beings indirectly. Begin by not harming sentient beings, and do whatever you can to teach dharma, contemplate dharma, meditate on dharma, gather monks, sustain monasteries, and build stupas and status. All your intentions and actions to increase merit will become causes of great enlightenment. If you do not have intentions that focus on the benefit of sentient beings or if you do but in your actions harm sentient beings, all your listening, contemplating and meditating on the dharma and seeming accumulation of merit will not be causes of buddhahood, and they would be brought there by mere luck.

很多时候,我们被外相所欺骗,我们自以为是在利他、是在修行,别人看起来,你好像也在这么做,但其实整个都是假象,虚假的一个相而已。所以,很多

时候我们真的要好好地反观、好好地反省,自己是不是真的在修行?修行是不是真的如法、清不清净?我们说在修行,当然不是为了欺骗自己,

是为了利益自己才修行,是为了有结果才修的。所以,真的不要再自欺欺人,要好好地反省和检讨一下:自己有没有真的好好在修行。

We must examine ourselves to evaluate whether we are practicing the dharma in a true way or not.

讲到这里,我想到一个故事,讲完这个故事,就讲到这里,明天会把第17个颂文后面部分讲完。可能还是要讲些故事,不然,很多时候,大家会觉得无聊。

这个故事跟密勒日巴大师有关。

This reminded His Holiness of a story about Jetsun Milarepa, deferring the remaining discussion of the 17th good deed to the future.

密勒日巴的故事

The example of Milarepa

密勒日巴在圆寂之前,留下了遗言,说:他没有留下太多东西,但他有一个拐杖,一个帽子,还有一个箱子,还有一块平时身上穿的布,他说那个要给冈波巴等等。平常他还有另外一根棍子,那个要给惹琼巴。等等,总之就说好了,哪些东西要留给谁。他只有这些东西。

所以,他就说,他的衣服都要剪了要分给什么人。不像现在我们说,这个iphone要给谁,电脑要给谁,可能东西很多,有的分。他因为什么都没有,一块布也得分成很多小块,才给很多人。

Before his passing, Jetsun Milarepa left a will and testament with his students. He didn’t have important or sacred things, merely a staff of aurura wood, a hat, and a cotton robe which he sent to Gampopa as mementos. There was another staff and another cotton robe which he sent to Rechungpa. He only had these few things which he left to his important students. He didn’t have a computer, or an iPhone, or many things as we do today.

其中有一个他说得很特别,他说:“我有一块金子,我放在关房的墙壁后面,你们不知道的一个地方。我死了之后,你们可以把它挖出来,然后大家分了吧!”

However, Milarepa said something strange, “I’ve kept a little bit of gold. Behind my retreat hut there’s a little spot in the wall – I’ve hidden it there. After I’ve died, get that gold and divide it amongst yourselves”.

弟子们就想:哎呀,密勒日巴居然有金子。他们就想“搞不好还真的有。”有的想说“不会吧,尊者怎么会有金子。”有的弟子想说:“搞不好有哦!因为有施主给过,所以他大概也留了一些。我们平常都想说,密勒日巴没有,但搞不好还真的有咧。”

接着一个就想:上师尊者——密勒日巴怎么可能有。还跟其他弟子讲:“你们不要这样乱说,不可能有的。”

When he said this, his students thought, “Milarepa said he had gold! We never thought Milarepa had gold. He must have some gold… maybe his sponsors gave him some”. Others thought, “How can a lama like Milarepa have gold? Don’t say such ridiculous things”.

反正最后,尊者圆寂之后,弟子们就聚在一起,去找那个金子。就到了关房,墙壁后面的缝中是真的藏了一个东西,可能应该是布包起来的一个东西,他们就把它拿出来,

大众面前大家打开。

After Milarepa passed away, his students got together and did what Milarepa said – they went to look for the gold behind the retreat hut. When they went behind the hut, there really was something hidden there. There was a bundle of tied-up cloth. And so the students took it out. They opened it up where everyone could see.

里面没有金子,有三块红糖,包在一块布里,还有一个他的纸条,还有一把刀子。 弟子们就想说:黄金在哪儿呢?先看一下他纸条写了什么。 写了什么呢?就说:“你们呢,用这个刀子把红糖分了,每个人分一点,那块布你们也把它剪了,尽量剪到最小,让每个人都分到。” 最重要的,后面有段字是说:“有些人说我密勒日巴有金子,这些人去吃屎吧!认为我密勒日巴有金子的人,吃屎去吧,你们!” 当时他才圆寂三、四天,其他弟子心情是很难过的,所以一看到纸条的时候,吃屎一看到,大家全都笑了。很难过的情况下,大家看到那段字都笑了。 为什么要说这个故事呢?因为我们会说:密勒日巴是一个非常非常苦行、非常清净的修行者。他大概是一个非常严肃的、不苟言笑的,这样的一个人,但其实密勒日巴不是这样的,他也常会开玩笑的。他是一个很放松,很自在的,他身上就只有一块布,所以你看他圆寂之前,还要留下这么一个纸条,给弟子们。

要像一般人,我们怎么可能还会在死前,留下这么一个开玩笑的留言。密勒日巴圆寂前还是中了毒吧,一般人中了毒怎么可能还想到说,这么自在地写下这么一个纸条呢?还可以写下这么一个开玩笑的纸条。他自己也很开心,也让他的弟子们很欢喜、开心。这代表了什么?就是过去的祖师们,这些大成就者们,不是我们所想的,像个石头一样,

不苟言笑,不是的。他们是非常的自在,非常的开朗的。这是一方面。 另外一方面来说,他其实是在测试他的弟子们。因为平时密勒日巴是个完全不贪著世间的,圆寂前说有

金子留下来,他弟子有的就怀疑了,就起心动念了“唉~怎么会这样说?”真的打开就没有金子,所以真的是一个他标准的弟子,当然就不会相信。但那些还不太信心稳定的弟子就想说:密勒日巴生前大概藏了不少,就不告诉我们。我觉得他是为了测验弟子,而做了这样的事情。 对密勒日巴来说,有没有金子一点差别都没有。 这不是说,别人供养他金子,他说:“哦!不要给我。这是脏东西,我不要。”他不是这样的,他不是在那里装模做样地说:“你不要给我。”他不是这样的,说“不要给我金子,不要给我金子!”。但是他内心真的是不贪著这个金子的。 说这个故事的原因是,透过他这个故事,我们也去想一下,最重要的关键是什么?就是我们一生当中,最重要的是什么?应该要去想一想。 好,大概是这样子。最后我们做回向。 Bamboo评论:大宝也是这样的,像他后来六月庆生时说的,即便明知中、美这两个极端恐怖政权不会让他再活着,更不会让他自由。他也还是那样认认真真地把课讲完,努力地提醒着Bamboo这个胸无大志的家伙要成佛。 佛经中说:诸佛为一大事因缘出现于世——不断佛种故。所以他就跟《大话西游》里的唐僧似的,只要一讲课,就不停叨叨“要成佛!要成佛!”。Bamboo这个只想当小弟的家伙,被逼的只能自个当老大——成佛了~(11/8/2022)

When they opened up the bundle, there was no gold.There were three lumps of jaggery, a letter, and a knife in a square of white cloth.

When students saw this, they exclaimed, “Milarepa said he had gold! Where’s the gold? We’d better look at the letter…”

The letter read, “Take these cubes of sugar, cut them with this knife into little pieces, and give a piece to everyone who is here. Then cut this square of cloth into little pieces, until the cloth is all used up, and give a piece to everyone present.

“I think there’re a few people who said that Milarepa has gold,” the letter continued.“Tell them to eat shit”.

This was a few days after Milarepa had passed and everyone was grief-stricken. When they heard “Eat shit”, they burst into laughter.

We think of Milarepa as a great master who practiced the dharma purely, undergoing many hardships. He’s a better person than we are, so we think he’s probably very serious. But actually Milarepa was very relaxed. He enjoyed himself. Even after he had been poisoned and was in physical pain, he was still enjoying himself – right up until the time that he died. He still played jokes, to lighten things up for the people left behind.

Another aspect to consider: Milarepa was testing his students. Usually, Milarepa had absolutely no attachment or desire for worldly things. However, some of his students heard “Gold!” and became suspicious. However there was no gold.

Mila was completely fine if there was gold or no gold.

This is an example that we should think about. What are the most important things in our lives? We really need to consider this.

Youtube 视频